Continuing the journey with Robert Mueller

In our first blog post, Robert Mueller chatted about his early days growing up on his family’s Napa Valley ranch. Situated in the Rutherford district of Napa, the farm was home to wine grapes–his first taste of the Napa Valley winegrowing industry.

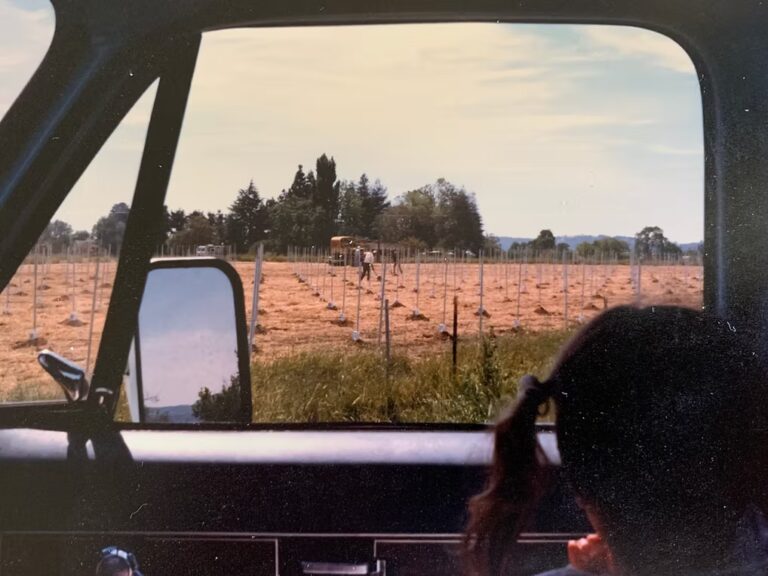

In that blog, we tried hard to paint a picture of these early days: tastings from the back of pickup trucks, more tractors on the road than cars, and more land open for cattle or planted to orchards than vines, and also, just happening to come across some good ole André Tchelistcheff Pinot Noir. It was a very different time!

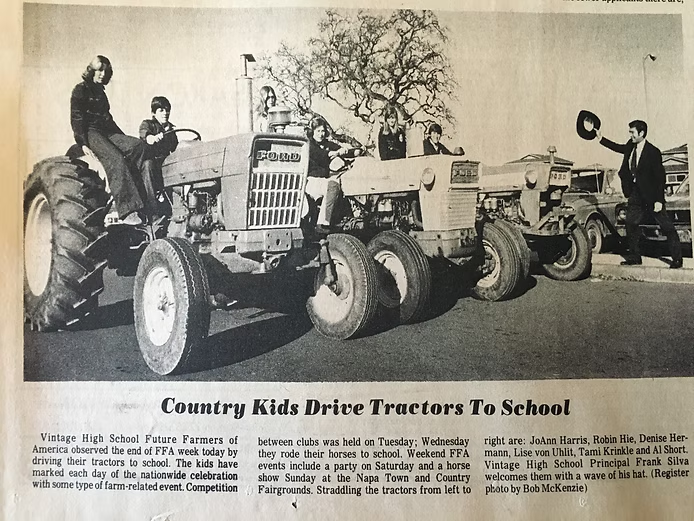

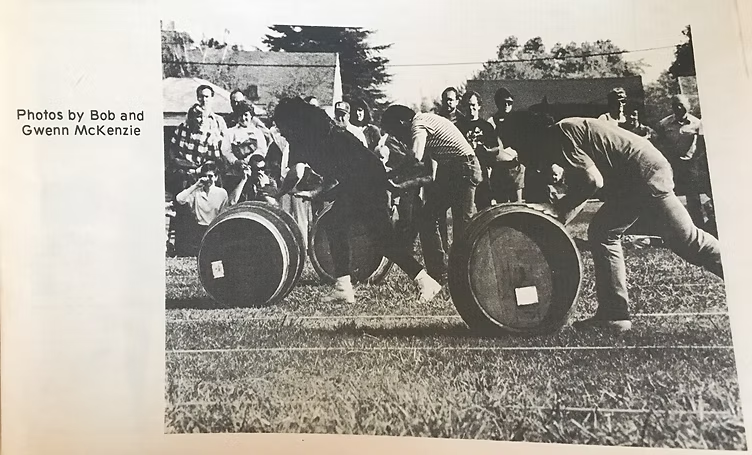

As much as we try to portray what it was like in those days, photographic evidence really is needed. Fortunately, my grandfather, Bob McKenzie, was a photo journalist for the Napa Register (our local newspaper), so we have some great photos from Napa Valley in the 1970’s & 1980 which is where our Blog Post #2 begins.

First let us set the scene: Tumble weeds and wine & kids driving tractors to school….

Above: Napa Valley Register photo by Bob McKenzie

Celebrating farming by driving tractors to school!

Above: Photo by Bob McKenzie in the Napa Valley Register

Local Napa Valley residents getting tumble weeds contained.

Below: Photo by Bob & Gwenn McKenzie in the Napa Valley Register

Local festival activity of barrel racing.

The small town of Napa Valley starts to ramp up and get the tumble weeds cleared out–wine comes into focus.

Sam: Some background about the Napa CoOp would be great, because I don’t think a lot of people know much about it. I only know a little from what I’ve heard from you in the past.

Bob: Ok. Actually there were two CoOps in St Helena. This was the southern CoOp and it was a group of growers that harvested and took their fruit to be processed. The resulting wine was purchased by Gallo back in the day. So it wasn’t really their own label that they had—It was more making bulk wine and selling it on the market and as far as I can remember it was always Gallo that purchased it, though there may have been others.

Sam: So you worked at the southern CoOp of Napa Valley?

Bob: Yes. It was a pretty old plant. A lot of redwood tanks and wineries within wineries. It’s actually now Hall winery there just across from Sattui. It…you know, it had been used for a number of harvests. I think the original name was Bergfeld winery. And again it had larger bulk production capacity that kind of enveloped that whole building. It had, like I said, a lot of redwood tanks. A lot of, I’ll say 20,000 gallon tanks. And the fermenting room that was outside, was all concrete. So there were like big, big concrete—like swimming pools (ha), that would hold like 40 tons…40 tons of fruit. And it had an old piston pump that you used to circulate them. And there were one or two jacketed tanks.

With the equipment that they had it was much more challenging to keep track of the fermentations, because as they create heat–which they do by the process–As the temperature rose to a certain level, if you didn’t chill them down they’d just go way out of control. And of course too warm of fermentation was not a quality benefit.

[And to help those reading a long in this interview, stainless steel tanks are the norm these days for fermentations in the wine industry. Most stainless steel tanks have jackets that allow winemakers to easily control temperature. As Robert mentions, fermentations give off heat, and regulating the temperature is crucial to creating a fine wine; too hot of a fermentation is problematic, too cold of a fermentation also problematic. Goldie Locks!]

Sam: Yes, fermentation temp is crucial!

Bob: So they had this big, heat exchange—a tube in a tube—and you’d take and hook up to the tank that you wanted to cool—And you’d chill it down but you didn’t want it to get too cold because then it would delay the fermentation [which was problematic] because that tank needed to clear out ‘cause you you needed the room for another lot [that would be coming in].

[Reader tip: Making sure a fermentation doesn’t stall out is important, especially if you still have more fruit to bring in and process. ]

Sam: I think that is something that is still very much an issue these days. Most recently in my memory for us was the bountiful 2018 harvest…

Bob: Yes. And there [at the CoOp] it was a production process and you had to really keep on it. So like one or two people that were there spent most of their time just monitoring the temperatures. It wasn’t that you couldn’t do something else in the mean time, but, you had to really be careful about it just from a quality standpoint. And the wines there were generally very very good. And they did have a label that they sold to growers–It wasn’t for retail.

Sam: Why was it specific for growers?

Bob: I think it was a perk for the growers to bring their fruit in, that they could have some of the wine that they produced. And a lot of it—I can’t remember the exact label—but, it was a red wine and a white wine. It didn’t go under a varietal name, but it was generally, the red was a zinfandel.

[These days, it is still very common for growers to include a case allotment in their grape contract. It is always a treat to taste the wines that people make from the fruit you grow.]

And it was really quite good. And they sold it in 750 ml, and also, in gallons. So a gallon for us was, too much to have in one sitting—

Sam: Ha! No…

Bob: Haha, it was very modestly priced so you’d—you’d take the gallon and break it down into smaller bottles and cork em, and it’d last forever.

Sam: At home?

Bob: Yeah. They did sell 750s I believe, but the economics of it were very inexpensive if you got it by the gallon.

Sam: Right. And did they allow you to bring your gallon jug back in to refill ever? or?

[Bringing in your own jug to fill was actually quite common back in the day. In these days of shelter in place, it just might make a comeback…]

Bob: No, I don’t recall that there at the CoOp. That was done up at Nichellini, you could take it up there. And that was very popular also, getting wine in gallon jugs. And again, it was not a negative from a quality stand point. It was not like it was really cheap wine, or you know, poor wine, it was actually very good wine, it was just in a larger container.

Sam: Just a different time… So when was this about—when did you start working there?

Bob: Well, on our farm we grew grapes and we took them to the CoOp. And this was in the 60’s—the late 60’s—and I started there for a harvest season in 1970. I think I worked there 70 & 71 and I’m not sure, maybe 72 as well. But again, for maybe a couple months—three months, something like that. And at that time they had a board of directors and it was maybe 8 or 10 growers, and my father was a director. My fathers name was David Mueller.

Sam: So you have some roots at the Napa CoOp. Your father was on the board, and you were bringing your fruit in and processing it for the bulk market.

Bob: Yes. And you know, again, harvest season, you always need more hands to do all of the work. During the off season it was only a 2 or three person operation there at the CoOp, and that included maintenance. But during harvest it would be a number of people and thats where I really saw the process up close. I think I had a really good teacher. He was really gruff but he was very experienced. He was an Acquistapace. I’m not sure its related. Maybe he was related to the ones down in Carneros I’m not sure… but his nickname was Rasty. Rasty Acquistapace.

Sam: And so you were pretty involved in all parts of the process there. Hoses, pumping, crushing, anything that needed to get done, you were involved in as far as production?

Bob: Pretty much, although I can’t say I ever ran the crushers. That was a job that I particularly—not that I wouldn’t have done it—but I didn’t really like that one because you were just running around like crazy.

[Bob transitions into explaining the jobs starting with what jobs were like in the field. His memory takes him to the VERY heavy lug boxes that were used to pick into…]

When we first started taking fruit to the CoOp, it was in 40 pound lug boxes. You know, when you picked in the vineyard, you picked into these lug boxes that were set on the ground. And then a flat bed would come by, and they got loaded onto the flat bed one bye one, and then they were taken to the CoOp. They did have a screw top conveyor to help move the Lugs—but all those boxes one by one had to be loaded on to the conveyor.

Sam: So that is like the original FYB?

[A FYB…. stands for: F*cking Yellow Bin. You see them down the rows at some vineyards during harvest. For vineyards with close spacing, or steep hillside where a tractor can’t really access, these bins are used. Some winemakers prefer these FYBs because they believe it to maintain the integrity of the fruit all the way from the field to the crusher. With fruit in 1/2 ton boxes that tractors haul, the bottom fruit can get squished and bleed out juice–the issue of oxidation begins as soon as the berry skin is compromised.]

[Bob smiles and corrects me–FBB is his preferred terminology. He continues…]

Bob: Actually it was 40 pounds, so heavier than the FBBs. And the FBBs would–they might hold 20-30 pounds I think. And you’re trying not to—you’re trying to keep the fruit in tact, so it’s like you don’t want any pressure on the fruit. And the lug boxes, the guys harvesting…they would pick and bring the boxes out and who ever is in the avenue would give them a little chip. Something like when you’re playing poker, you have chips. So they’d give out a chip and at the end of the day I guess they would see how many lugs they filled and that would base their wage that day. So those guys are flying through the vineyard and there was a lot more walking than there is now.

[In some cases, FYBs require a lot of walking–placement of the FYBs and walking them out to the end of the row. With tractors and macro bins (1/2 tons), walking can be less as the crew moves along with the tractor. Robert explains…]

So we had to walk all the way in—what is that 13 vines times 8—thats how many feet you’d have to walk in and then you’d pick that row out. And so you’d be carrying the lug box partially full from vine to vine until you got if full, take it out to the end of the row and then have to go back again and finish that row. So it was pretty difficult.

Sam: Picking today is hard work of course, but I can imagine all the walking with those especially heavy lug boxes. Much heavier than the plastic picking trays that people use today.

Bob: Exactly. And when it got to the winery the driver had to take each one of those boxes and dump it into the hopper. Which, was…very labor intensive. You’d get a really good work out. And then they switched to gondolas, which would hold 2-3 tons and you could settle up very close to the crusher and it could be hoisted tipped and dumbed. It made it a lot easier, but it was still a lot of work.

[Gondolas are yet another vessel that wine grapes are transferred in. Gondolas are still used these days for large ton picks at some vineyards. I personally have no experience with gondolas here at McKenzie-Mueller, but they carry quite a bit of weight and therefore (sometimes) will see a good amount of juice (from the berries at the bottom being squished) being dumped into the crusher along with the fruit.]

Sam: As far as the small boxes, they’re really great at keeping berries in tact—switching to the gondolas which holds a lot more fruit in one thing, so you’re dealing with a lot of juice being squeezed out from the berries at the bottom.

Bob: Sometimes, yes.

Sam: Which is kind of opposites as far as grape integrity at arrival to the crusher goes…

[Bob transitions into talking about brix. Brix is a sugar measurement that is used in winegrowing. The brix level can give winemakers an idea of how firm the berry will be, which is good to know depending on wether you are transporting grapes via FYB, Gondola, or 1/2 macro bin.]

Bob: …Which reminds me of a time when, you know, you’d be paid a bonus if you’re with in 22-24 Brix. If you were under you’d be docked, or if you were over you’d be docked. So everyone tried to get that 22-24. So later, when I was at Mondavi, the Brix level was raised, so having something 24, 25, 26—was still able to handle it. But we had some lots that came in that were 29, 30, 31—

[Some winemakers swear by 24-26 brix, others swear by 27, 28, 29. There is a lot of passion surrounding this topic–ha! Brix of course is just one tool in the tool belt of helping the winemaker ultimately making the decision to harvest…]

Sam: Oh! I thought that was something that was new to my generation—the 29, 30, & 31 brix…but you’re saying this has been going on for a while…

Bob: haha—yes… and, one grower was so, I don’t know… very creative… and he had fruit that was maybe 30 brix. And he went over to a near by property and hooked up a garden hose…

Sam: haha, wow…

Bob: …and did his own dilution. He got caught… not a good thing.. but there have been worse. I’m sure.

Sam: mhm. yeah, those dang growers are always up to no good!

[We are growers 😉 and winemakers!]

Bob: Haha. Hey, what happens when you’re the grower and the winery?! You have to sneak it in and then turn and look away—ha!

But..getting back to the CoOp…they had a sugar stand. And the state provided a person that would ‘stab’ the gondolas, or take bunches from boxes—if they were in lugs—and do a mini crush. They’d record the sugar and wait. But you know, I have to say…it was a very simple operation, but I think very efficient. It didn’t have a lot of technology, but for making wines, it did pretty good. For the laboratory there—Gallo supplied a person for the lab—and the one I remember was Walter Schug.

But, they had two 50,000 gallon tanks. And I don’t think they were stainless. And one 100,000 gallon tank. and uh, when things got towards the end, and you didn’t have room sometimes you’d be taking all the white juice and running them through this in place line, into this big 50,000 gallon fermenter. So you had, like 35,000 gallons of juice fermenting in this tank. And the lees at the bottom, at the very end–because you’d rack the clear wine off—You’d have to push the lees.

[Reader tip: lees are dead yeast cells, left over yeast, or other particles that accumulate at the bottom of wine holding vessels. It’s consistency is typically runny/gooey when you have freshly racked the clean wine off of it.]

So you’d have to go into the tank with a squeegee, and you’d have to push the lees to the valve and use a piston pump, and pump it out. And sometimes—you know the regular work boots—well [the lees] were at the top of your boots, so you had to be careful that you didn’t bend over too far or the lees could go in right when you got into the tank—and you might be in there for a while.

It wasn’t done that often but.. It’s kind of peaceful and quiet. You’re kind of sittin’ in this tank. And somebody’s there to make sure you safe. But uh, after 35 minutes to and hour you’d be done. But in that 35 minutes to and hour, it was very peaceful. You didn’t have to run around.

Sam: Definitely a good mix of chaos and peacefulness. Seems like it just depends on which station you’re at.

Bob: yes, very much so…

Until next blog post, Cheers!